I got what may be the most important phone call of my life today: from my urologist, Dr. Hashmat who practices in Brooklyn. He told me that the prostate biopsy that he did a week ago last Monday came back “normal.”

I got what may be the most important phone call of my life today: from my urologist, Dr. Hashmat who practices in Brooklyn. He told me that the prostate biopsy that he did a week ago last Monday came back “normal.”

“You’re normal,” he said. “I know you must be anxious to hear this.”

I felt like someone had handed my life back to me. This huge weight had been hanging over my head and I’d been trying desperately not to feel it, pretty much living in denial, trying to go about my business as if nothing were happening. Twice, the first week after the biopsy was done, I’d woken up about 2 a.m., jolted from anxiety. I got up, walked into another room, sat down on the couch, and tried to keep from going out of my head. I kept telling myself how fortunate I’d been. I’d been able to live my life almost exactly the way I’d wanted to live it–had done what I had set out to do–been able to write books, poetry, songs, plays, articles for God-knows-how-many magazines. I’d given a number of people pleaure in their lives–I was very fortunate. But even more fortunate, I’ve been loved, really loved by some wonderful men and women. My partner Hugh, my closest friend Robert, my sister, our friend Susan, my wonderful best friends Jeff Campbell and Marc Collins, who is are longer alive, only two of the terrible victims of AIDS; there are others, but that is what is important in the long run, being loved, being able to feel it and know it.

I was so lucky. By sheer fortune, I found a doctor who started to see that my PSA level was rising: it was 4.2.–7 is prostate cancer–so she sent me to see Dr. Hashmat, an excellent urologist, and he looked seriously at me and decided that we needed to do this biopsy. We did it in his office. It was painful: I can’t lie about that. Even with a large dose of anesthetic, it felt like this rattle snake was running up my ass and biting me in there. He took 7 samples from various sites on the organ, and then told me to wait until the anesthesia wore off. I was dizzy and a bit nauseated. Robert came to Brooklyn to accompany me back to Manhattan, and then the Bronx. Hashmat had warned me that I would see some blood in my urine, my stool, and my semen. But I wasn’t prepared for how much blood would appear the first time I urinated. It was scary, and it continued for the first day or so. My groin felt terrible, like I’d been kicked in it; but I did not want to feel that, all I wanted to do was not be worried about it. Just try to . . . be someplace where I would not have to think about that word cancer at all.

My father had died of colon-rectal cancer at the age of 42. I was 11 when he died, and never was told what he had died of. Back then, in 1958, in the Deep South, you never mentioned words like “colon,” “rectal,” and “cancer” to kids, as if there was something obscene in the Southern mind about all of that: it was too involved with the real body, and everybody knew where that could lead: to the truth itself, something no one could venture into when I was growing up.

The truth was absolutely shameful, so you stayed as far away from it as possible.

We’re still staying away from the truth about so much, but I am grateful for the candor and frankness people now have about things like prostate cancer.

I joked to a friend that I never knew what the word “prostate” meant until I was about 36. Prostate was a part of that nether region that was not supposed to be broached in polite company. I knew that there was a pleasurable aspect to it–ask anyone who’s into anal sex–but exactly what the prostate does, and often what it leads to–anyway, I had little idea.

I do now. And I’m deliriously grateful that I’ve dodged this particular, scary bullet, to put it mildly. I’ve now got the rest of my life before me . . . but then, in truth we all do.

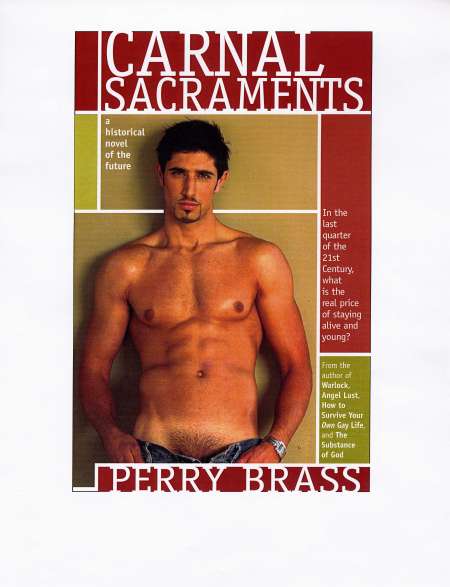

Perry

www.perrybrass.com