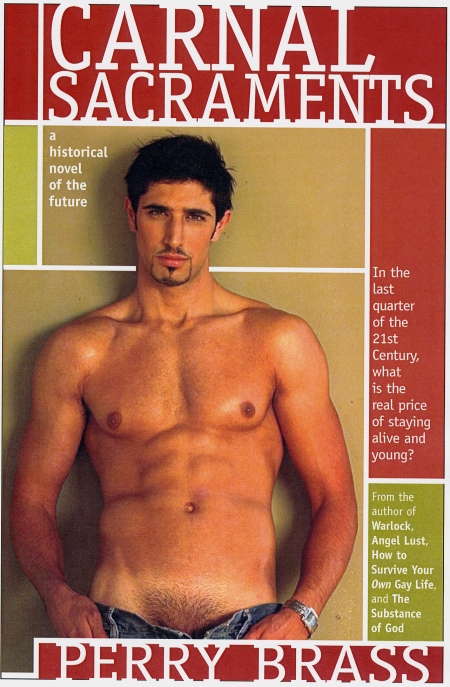

My newest book Carnal Sacraments, A Historical Novel of the Future, just came into the world. Actually, it arrived from the printer on June 18, 2007, but I’m still getting used to it. It’s like having a newborn infant in the house, and the question is what do you do with it, except admire it, or maybe go a little crazy about it?

Actually, giving birth to this one was really hard. It’s my fourteenth book, and I can’t say that they get easier all the time. There was a time when I was on a real roll with books. I published one a year (and occasionally even two) for about ten years. Then I started to realize something. There were places I wanted to go in my books that did not just come off the top of my head, and these places took a lot of digging and gouging to get to. This is not to say that some of my earlier books were rinky-dink. But the first few books, like the Mirage series of queer science fiction novels (Mirage, Circles, and Albert or the Book of Man) had the delicious satisfaction of being born easily. They just literally came out of my mind pretty much fully formed.

In fact, Mirage, my first published novel, took, from soup-to-nuts, from an idea I had in the shower to a finished, published book, exactly six months. I mean, I worked like I had never worked in my life—with literally twelve-hour days of work on it—but it really was just this fortuitous thing falling out of my head, and there are parts of it today that embarrass me. Some of them are simply just bad English. It was copyread instead of being really edited. But readers loved it, and I was lucky in that the hero of it became almost a new “type” of gay hero: not wounded, totally sexual, compelling, visceral. Greeland was wonderful, and I had readers who told me they wanted to marry him.

But Carnal Sacraments, my newest novel, was hard birth. Part of it was that I began three other books before I realized this was the book I wanted to stay with and write. I was kind of dating the earlier books; it was all enthusiastic, then they’d stop someplace and it was time to begin with someone new. But this book dealt with things that I needed to talk about. Things that are already here, even though the novel is set in the fairly-near future, the year 2075, in world that dominated by one economic system: global capitalism. A system of one huge market made up of interlinking markets and currencies, capital pools and worker pools. Where the most important thing is simply keeping money in one constant state of movement and aggressive growth, and only people who increase wealth and the flow of it are considered valuable. So that means that helping people is out (forget it, you doctors, teachers, health and education people—you don’t raise the ante one bit!), and only the most rapacious carnivores get to sit at the table and slurp.

So, I began three other books, who may come to birth later, and also produced a screenplay for my novel The Harvest, which landed on the world with a total thud and a whimper. As in, forget it. Hollywood is so closed it makes Fort Knox look like a shopping mall. But I enjoyed doing the screenplay. I was snookered into it by a young director/producer named Daniel Ferrands who read The Harvest and told me he’d “option” it, but it would be better to have a real screenplay to start off with. So I jumped into the screenplay, and felt that in some ways it was actually better than the novel: I could really think visually about it, and I enjoyed that. But, after the screenplay was finished, Danny jumped ship, and went off to some other island (i.e. other gullible writers to make promises to), and so that was over, and I was back to my first love, the next novel.

I can’t actually tell you though how or when the idea for Carnal Sacraments came into my head. Usually novels begin for me with a very specific feeling associated with a moment in the book. It’s an actual physical situation—and suddenly I’m there. I’m inside the book, before a single word is written. But I can’t remember exactly when that happened, although I could feel that moment that became the first scene in the book, when Jeffrey Cooper is attacked, seemingly randomly, on the platform of a public train in Germany. He’s been floating inside his head, trying to keep from becoming stressed from the onslaught of a packed, pushing rush hour at the public transport (“pubtran”) station of the future, where the trains glide in noiselessly, and everyone is so absorbed into his own frantic, speedning digital world, that no one pays any attention to the fact that a man is being viciously punched on the platform.

I could feel that moment, and right after that, at lot of the plot started to unfold. There was the idea of people being completely buried literally alive in their work, so that almost none of their real personalities ever surfaces or survives: They are their jobs. They have no identity outside work; they can only survive this way. Any other approach to living becomes impossible. Against this tide, I placed another character, a very troubled painter named John van der Meer, a Dutchman living in Germany and feeling at heart as alienated at Jeffrey Cooper, who is American, from Alabama, but completely a part of the new, all-reaching global economy. These two men seem to have almost nothing in common except a strange need for one another, which they will soon find.

The book is set in a truly internationalized and very Americanized Europe, with Germany the center of it. It is a Germany that becomes almost more American than America, because America has taken so many steps backward (because of advancing religious fundamentalism) that the nation has become a Third World country, lagging in fact behind the Third World, which, educationally, has stepped ahead. So some part of the novel takes place in India, an India that is schizophrenic in its super-advancement on one hand and its ancient culture and remaining poverty on the other.

But every country is still connected to one vast global economic system, tied to the culture and religion of consumerism. People are now united only in customer relationships, becoming the consumerate rather than the electorate, and style is now substituted for any form of personal belief and expression, be it religious, ethical, or otherwise.

The first draft of Carnal came about fairly smoothly. I think it took about 9 months, and then came all the subsequent drafts, perhaps eight or nine of them, during which the book went through some fairly radical changes. I changed the tone of the book, brought in new concepts that held the book together—especially the idea of “style as domination,” and I brought in Harold Cooper, Jeffrey’s father who commited suicide. He is never actually in the book—but is only seen as a sad ghost, as the being that Jeffrey could never approach, but who approaches him in the end. I brought my own upbringing in the South into it, and also that of my partner, who is actually from Alabama. I’m from Georgia, and having grown up Southern and Jewish, had a very different upbringing than he did.

You can now get Carnal Sacraments at most gay bookstores like Lambda Rising in Washington, at TLA Video, at Amazon (http://www.amazon.com/Carnal-Sacraments-Historical-Novel-Future/dp/1892149052/ref=sr_1_1/105-5536128-3456421?ie=UTF8&s=books&qid=1182525317&sr=1-1), and at Barnes and Nobles. Or you can order it from my website, www.perrybrass.com. Any way you get it, it is one way of sharing in that wondrous situation called the “birth of the book.”